Measuring the business value effectiveness of external technical services

A case for ERP maintenance and support outsourcing

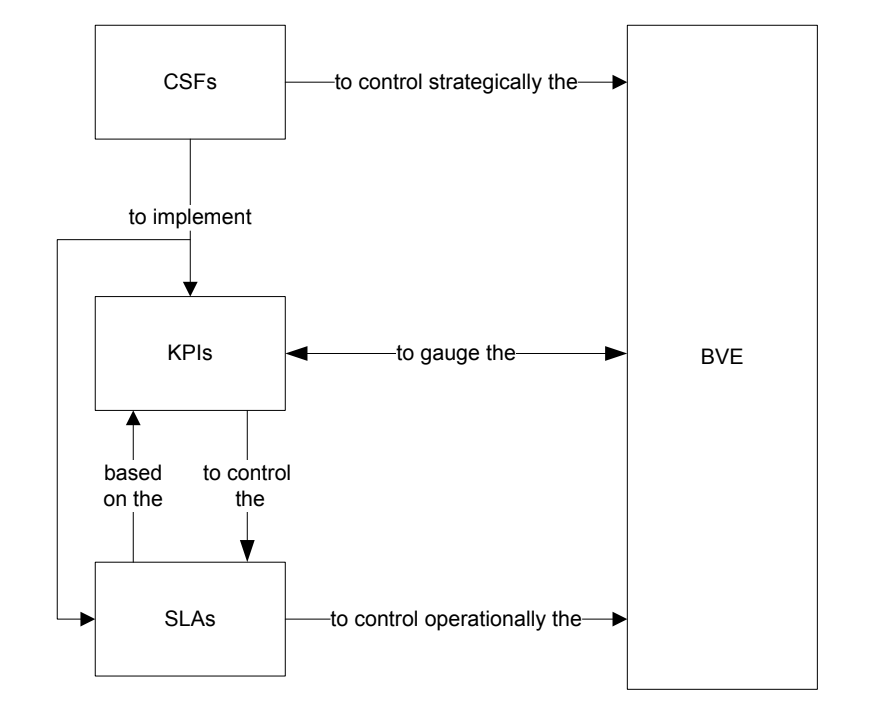

In this article a novel business value efficiency (BVE) model is proposed through the identification of eight critical success factors (CSFs), pertaining to the outsourcing of ERP maintenance and support.

Introduction

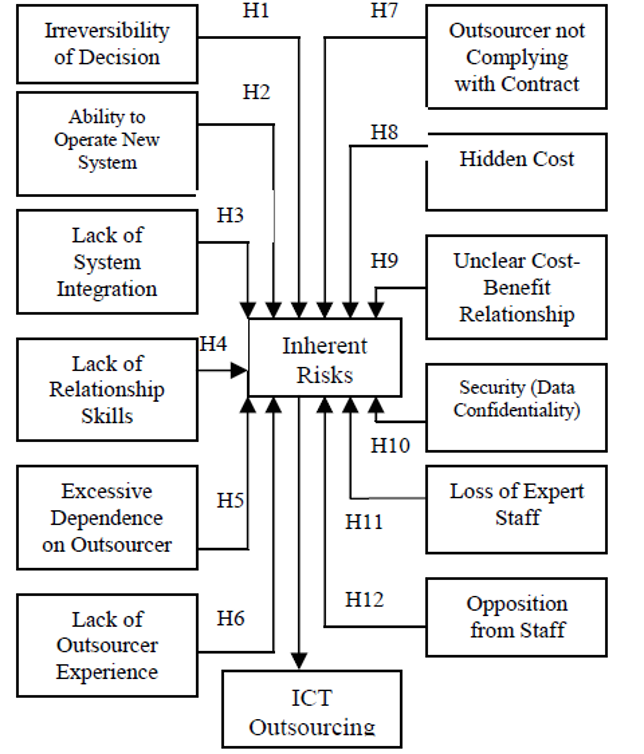

Service providers must demonstrate clients the strategic advantages of outsourcing to boost trust and collaboration. Outsourcing business critical processes is sought to leverage external expertise while allowing internal resources to focus on core business processes. From a technical perspective, the upkeep of an ERP system is normally considered business critical and yet not central to the core business. The shift from inhouse to outsourcing is compiled in a service model which requires time to yield its benefits realization. Furthermore, an outsourcing venture introduces multiple risks as defined in figure 1. Throughout the journey the client and service provider (ITO or MSP) will increase the trust and collaboration thus resulting in increased maturity. To measure the effectiveness of such strategic decision and ensure transparency, the client and service provider need to measure the business value effectiveness (BVE) of the service model. Without proper performance monitoring and alignment with the company’s overall strategy, it’s impossible to gauge the success of such service model. An outsourcing service model provides various benefits towards ERP, especially if an IT service management (ITSM) framework like ITIL is adopted.

Proposed model

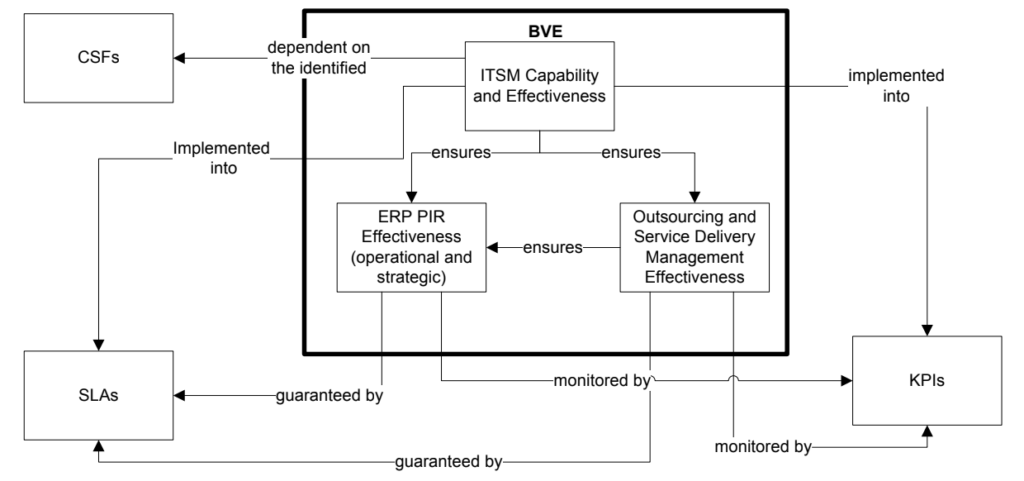

Business Value Effectiveness (BVE) determines how the ITO is able to realize the ERP Post-Implementation Review (PIR) effectiveness through IT Service Management (ITSM), which for this particular case study is ITIL. The ITSM determines (a) the service availability and (b) quality required for operational effectiveness, as well as strategic effectiveness brought by (c) service delivery and (d) outsourcing management. Functional ERP post adoption is measured on two pillars, specifically scalability and flexibility. The conceptual model presented in figure 2 below, can be further fine grained within the specific case study to gauge the business value effectiveness of outsourcing ERP maintenance and support.

This model demonstrates that proper (a) ITSM capability and effectiveness, (b) ERP PIR effectiveness is guaranteed and hence the (c) BVE can be measured from an (d) ITSM readiness, awareness, and capability test. Although many professionals might be familiar with ITIL related KPIs, analysts need to focus on the critical success factors (CSFs) which determine the BVE of an outsourcing model.

Critical success factors towards IT outsourcing business value effectiveness

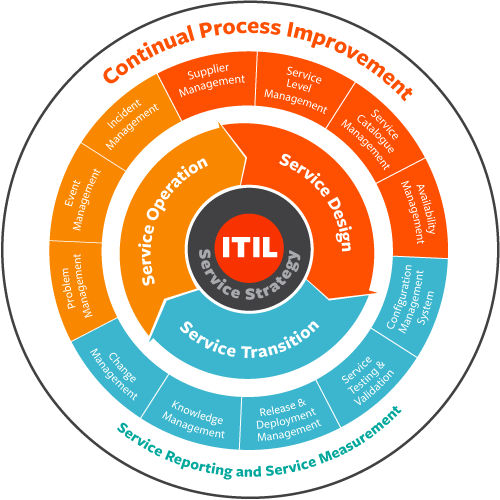

CSF 1 – Implement and adhere to an ITSM framework

The ITO organization should implement an ITSM framework such as ITIL because it allows the ITO to focus on the client’s desired outcomes being cost reduction, improved service quality, lower business risk. Through the alignment of client’s corporate strategy with the service strategy, the ITO can tailor a service design which fits the client’s requirements and allows the realization of benefits. The continual service improvement (CSI) is the catalyst to improve the service operation and advance the service transition. Through CSI, the service design and strategy are also updated according to the client’s requirements. The implementation of SLAs, allow the ITO to report to the client its ability to manage the below core concepts of such ITSM.

The service model adopted should be based on the client’s requirement. The implementation of an ITSM framework is not enough to guarantee business value effectiveness. Hence the ITO should demonstrate its adherence to such framework through:

- Regular assessment from an external body, which schedule is specified in the SLA. The report from such body is given to the client for review.

- Re-engineering of internal and external processes to meet changes in the framework adopted . These updates should be continuous and demonstrated by metrics in an IT dashboard and related to a KPI such as the ITO’s ability to manage the business interface.

- Training of staff on a continual basis. The SLA might specify that all ITO staff should be ITIL certified.

- Usage of ITSM compliant tools, KPIs and metrics as established in the SLA.

- Continuous communication between the client and the service provider through channels specified and defined in the SLA.

IT Service Management encompasses the traditional function of IT management together with business-oriented service support. In another research, ITSM is defined as a “provision of quality customer service by ensuring that the customer requirements and expectations are met at all times” (Tan et al, 2009, p. 1). By implementing a Service Delivery framework, the service provider is showing a commitment to provide the service with professionalism using industry best standard practices. This will facilitate the service delivery and management of the IT function and will help the client to focus on strategic affairs rather than the day-to-day operations. In this way the client and the service provider can focus of providing an augmented service delivery as needed through continuous management and negotiation.

CSF 2 – Identify internal and external requirements to formalize SLAs

The Service Level Management process is focused on (DuMoulin, 2007, p. 26):

- The identification of the client’s requirements and service

- The measurement and reporting of service delivery provided against such requirements and services

- The identification of how the service or the process of delivering such service can be improved.

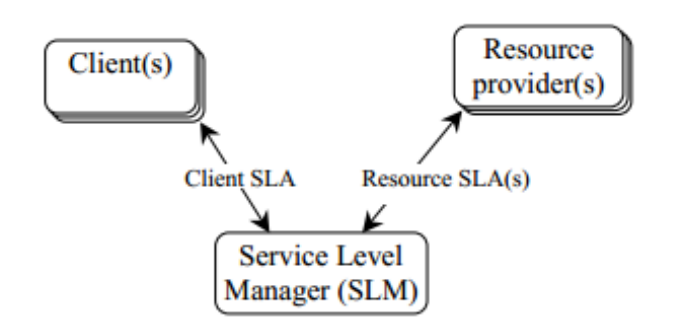

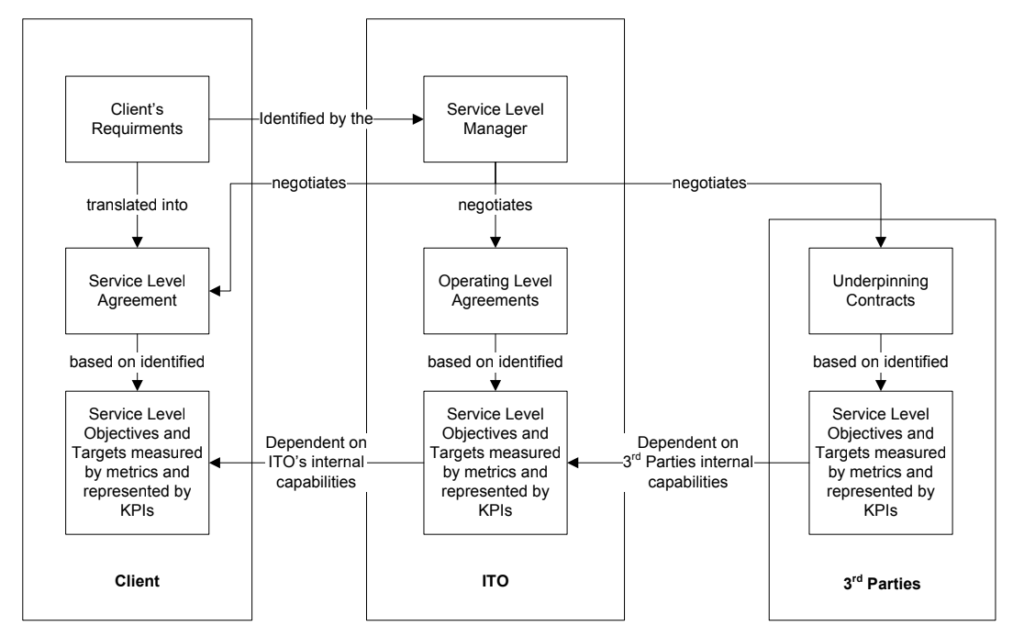

Dan et al. (2004), explained the importance of a Service Level Manager in the creation of such service level objectives. The Service Level Manager (SLM) needs to create an abstraction from the high level requirements of the client to low level specifications in terms of functions such as availability, security and responsiveness. The importance of an SLM in the discovery of requirements and formalization of low level specifications is further confirmed by managing client objectives which might also imply aggregating resources from multiple resource providers.

The ITO’s ability to conduct the maintenance and support service provision is most likely to require external support, primarily from the ERP vendor but also from other third parties. These may include professional ERP support specialist and other software supplier/vendors which are contractually responsible with system interfaced or integrated with the ERP system. These may include hardware and network vendors as well as consultants and/or auditors to ensure successful service delivery.

The discovery of such parties needs to be carried out during the implementation phase, so that the importance and risks of each supplier are identified, assessed, and measured properly. The Service Level Manager needs to identify the resources required from such parties in order to meet the targets, requirements and achievements within the Service Level Management process. Also, the Service Level Manager should evaluate the ITO’s internal capabilities to deliver the required level of support. After such analysis, the Service Level Manager can eventually determine the service levels that can be delivered and which are defined as objectives and targets in the SLA/s.

CSF 3 – Negotiate Service Level Agreements

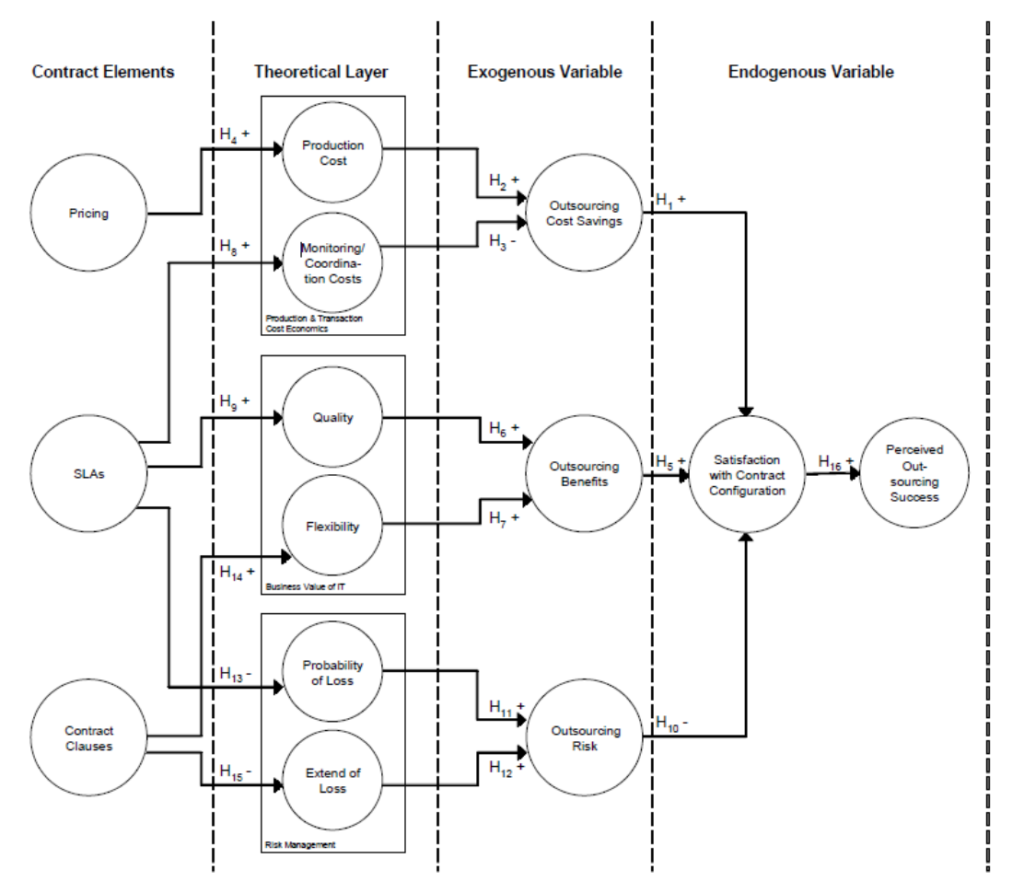

The quality of an outsourcing contract is by itself an important factor for the success of the outsourcing venture. Elements of such contract include (1) terms and conditions, (2) pricing structure and (3) service level agreement (Gellings, 2006). These elements constitute the efficiency of a contract to deliver a particular service or set of services. Hence these constructs are main drivers to the realization of a client’s expected benefits.

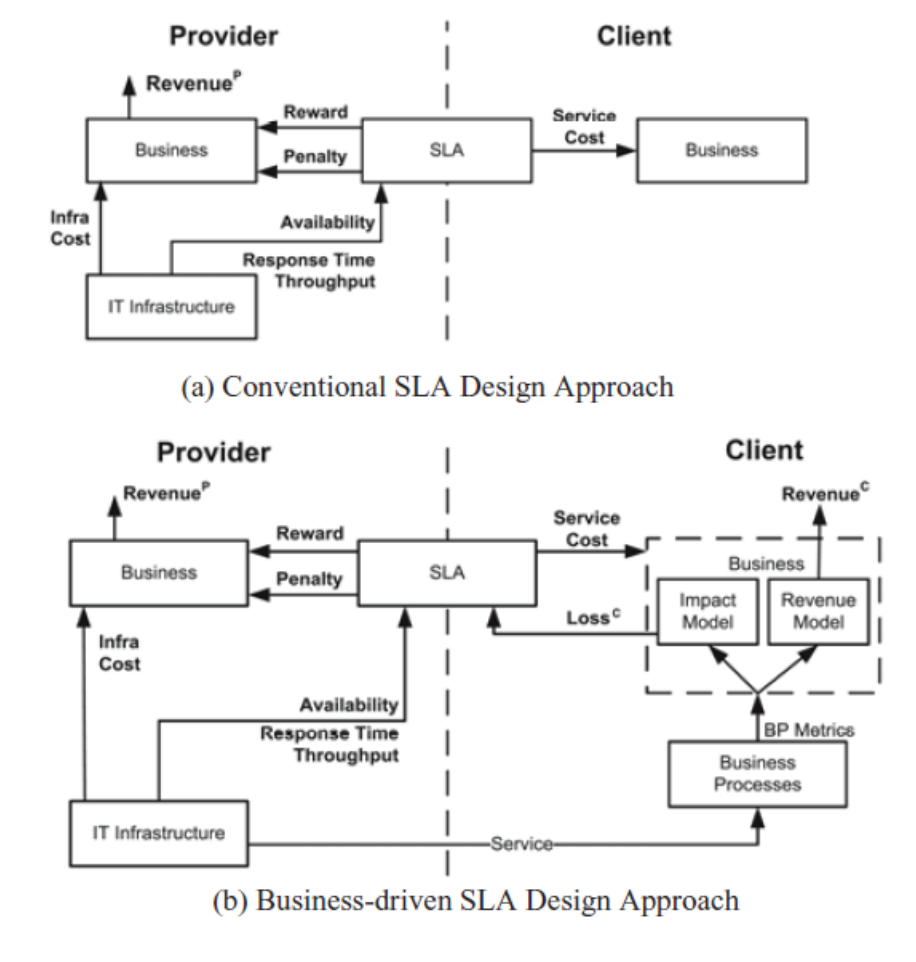

An outsourcing venture is purely based on trust. Such trust is not symmetrical and hence the ITO should demonstrate that its main interest is in realizing the client’s benefits. The design of an SLA can be a critical factor is the entire outsourcing lifecycle. Urikova et al. (2012) distinguished between conventional SLAs, where the focus of the ITO is on the realization of its own profits, and business driven SLAs. The latter design approach, promotes trust norms and enforces the relationship amongst the parties by incorporating rewards or penalties based on the performance of the ITO. Business-driven SLAs are proven to contribute towards improved profits for both parties.

In order to guarantee a level of trust and commitment with the client, the ITO should be committed to align the service objectives with a reward/penalty system. Another important element in an SLA is the introduction of a liability clause for addressing compensations for losses (Gellings, 2006). Such a clause is necessary to mitigate situation of negligence, whereby an exit clause can be triggered if the service objectives are not met on consecutive periods. To gauge such performance, KPI’s should be in place to reflect the above. The below indicators should be included in an SLA:

- Quality of work

- Volume of work

- Responsiveness

- Efficiency

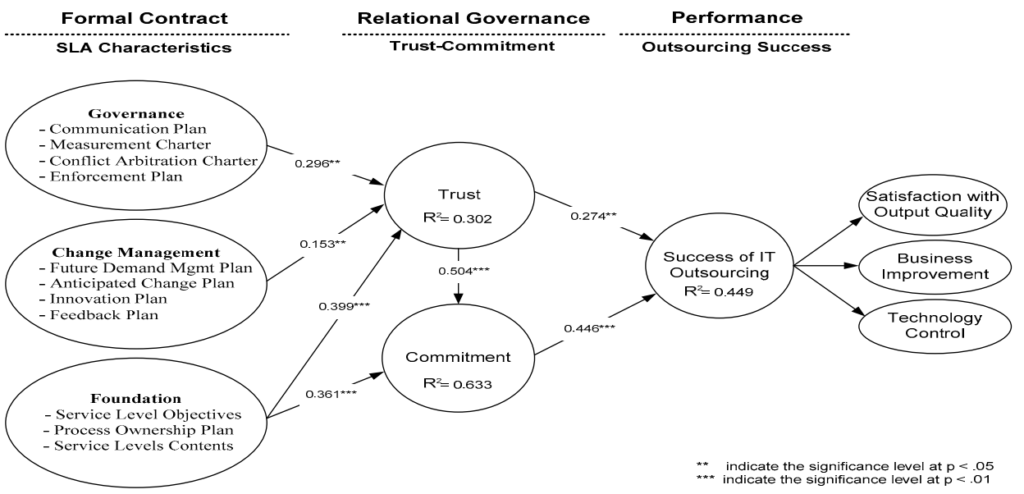

Furthermore, the SLA cover the following service assurance topics, specifically (Goo et al, 2007):

- Governance – Defining ways of communication, measurement, conflict arbitration, enforcement, and quality as defined by IT and Data governance mechanisms

- Change management – Providing provisions for changes to the service, future demand, and anticipated innovation

- Service foundation – Service level ownership, process ownership and service level contents

The quality of a service provision can be drastically improved through the incorporation of behaviour-based objectives in conjunction with output-driven objectives (Gellings, 2006). Behaviour-based objectives may include elements such as SLA/QoS forecasting that monitors potential SLA violation by predicting when an individual SLO could be expected to violate its SLA limit. It is important that any SLA fosters relationship management through trust & commitment, thus filling the gap between a formal contract and relational governance.

CSF 4 – Establish Underpinning Contracts

The establishment of underpinning contracts with third parties is directly dependent on CSFs 2 and 3. As explained by Gottschalk and Solli-Sæther (2005) the ITO has to integrate and exploit strategic IT resources from vendors together with its own resources to produce competitive goods and services which are beneficial for the client. As per figure 4, the Service Level Manager needs to identify the client’s requirements, identify the internal capabilities and identify external resources. This exercise should be done prior the actual definition of the SLAs with the client. The SLM needs to align the targets from the external resources and the internal targets and then define them in the service level agreement. Figure 8 provides a high level overview towards the development and alignment of service level agreements (SLAs), operating level agreements (OLAs), and underpinning contracts (UCs) with third parties.

In this way, an abstraction level is created whereas the client is not interested in the agreements between the ITO and external resources. However, the client has the guarantee and confidence that any issues will be resolved within the targets, irrelevantly if the issue will be resolved by the ITO itself, external resources or with the intervention of both internal and external resources.

CSF 5 – Establish Operating Level Agreements

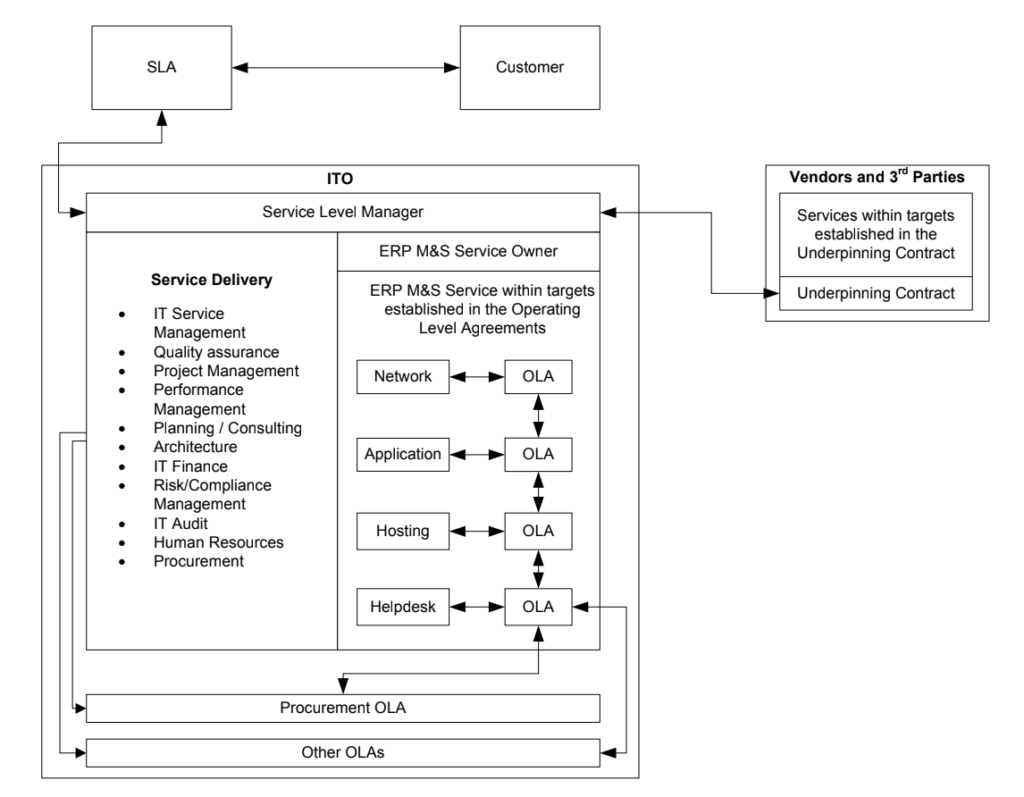

The Service Level Manager (SLM) needs to align the client’s requirements with the ITO’s internal structures so that internal work procedures are followed whilst service targets and objectives are achieved.

Operating Level Agreements (OLAs) are internal work procedures and sometimes these may comprise the Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) themselves. Such OLAs should eliminate the physical or virtual barriers within the ITO/MSP itself. Rather than having every functional team focused on its own objectives, OLAs ensure adherence to SLAs. Therefore the benefits of OLAs is that it aligns the ITO’s internal work procedures with the targets established in SL, thus focusing on the service being provided rather than the functional elements defined in the service delivery. The OLAs include metrics to ensure that work procedures are aligned to the SLAs. Such metrics may include response time, application availability and integrity of data or reporting.

CSF 6 – Establish metrics

KPIs and metrics should be defined and agreed in the agreement documents being SLA, OLAs and UCs. The KPIs and metrics proposed should be measurable and auditable. KPI’s should be focused on the business context rather than the technical measures being provided. Such metrics and KPIs can be formalized through prior identification of service level objectives as dictated in the Service Level Management and explained in CSF 2. These metrics should be agreed with the top management and their reading be discussed in governance and SRM meetings as established in the SLA. The KPIs utilized in a service model related to ERP maintenance and support operation may vary depending on the business modules within the ERP system.

ERP systems are knowledge enablers, because they contain relevant information in the right time. Therefore KPIs related to ERP systems should impact a business decision in some time scale (Skibniewski et al., 2009). KPIs should be associated to business processes and financial status. Two different categories of KPIs should be utilized to ensure prompt and effective business monitoring. These categories are (Skibniewski et al, 2009):

- Hard time-sensitive KPIs, which need corrective decision to be taken immediately due to their negative business impact; and

- Soft time-sensitive KPIs, which degrade the performance of the service, provided but are not top urgent and hence the corrective decision can be taken in a short period (business quarter).

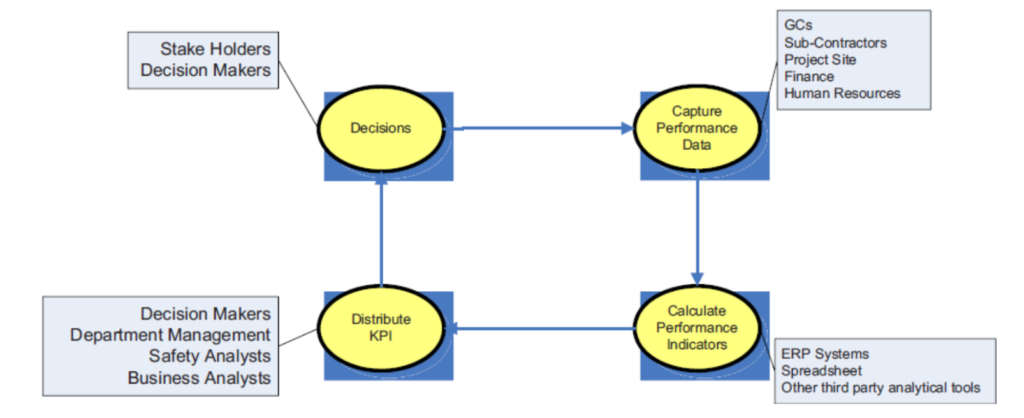

In order to have the correct KPIs in place, the data should be captured, calculated, and analyzed to provide meaningful and relevant indicators. Once the KPIs are established these need to be distributed to key stakeholders whereby decisions are taken based on such indicators as per figure 10, hereunder.

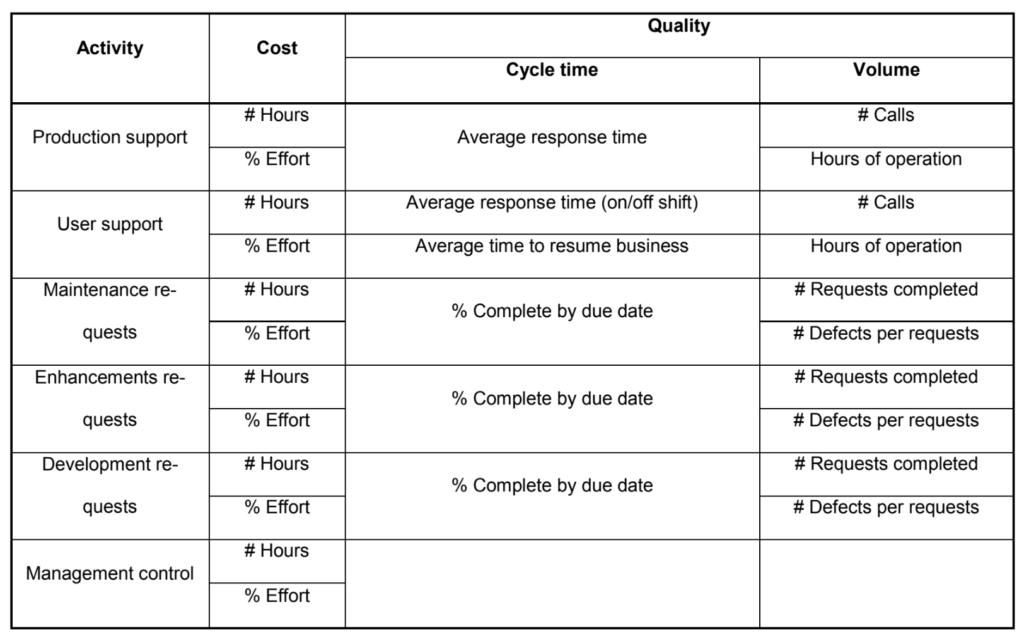

Triggers associated to each metric should be in place so that issues are resolved in due to time, thus guaranteeing Quality of Service (QoS). QoS differs from customer satisfaction especially “where perspective of quality and satisfaction may differ significantly from client management” (McGuire & McKeown, 2000, p. 400). Table 1 demonstrates metrics related to the QoS which should be measured by the ITO/MSP.

The need to conceptualize metrics into business-related KPIs, arises due to the over abundance of raw data generated from metrics. Such sheer volume may lead to difficulty in the interpretation and meaning of such data. However, if such data is collated and represented in terms of indicators, data is transformed into information and subsequently to knowledge. Every metric, should provide insight to a particular KPI established within a specific SLA. Furthermore, each metric should be at least two dimensional, whereby it gives a value over a period of time.

In fact, every metric can provide insight on 4 major categories:

- Volume of work, such as number of Configuration Items which failed.

- Quality of work, such as defect rates, standards compliance, technical quality, service availability and satisfaction.

- Responsiveness, such as time-to-implement, time-to-acknowledge and backlog size.

- Efficiency, such as cost/effort efficiency, team utilization and rework level

The ITIL metric tree proposed in figure 12, demonstrates how metrics are developed and measured from different components to ultimately derive business related KPIs and IT related KPIs. The business related KPIs are to be reported on corporate dashboards whilst IT related KPIs are reported on IT dashboards. Both KPIs should demonstrate the ITO/MSP’s ability to provide the service and should also serve a starting point to take decisions and carry out improvement.

CSF 7 – Review Service Level Objectives continuously

Organizations do not live in a vacuum whilst changes are frequent. The changes affecting the client should trigger changes to the service model adopted by the ITO. Changes to the service model and/or delivery can be affected by several events such as restructuring, technological changes, strategy changes, new opportunities, and external factors. In view of the above, the ITO/MSP should clearly define scheduled cadences to review the SLAs and Service Level Objectives (SLOs). Changes to the SLOs may automatically trigger changes to the service design or the service model depending on the impact. Also such cadences should be assessed and measured by metrics such as number of SLA/SLO reviews over time.

Service Level Objectives need to be reviewed on a particular schedule in order to determine how the service delivery can be improved. By means of reviews and/or triggers the ITO/MSP ensures that support (Opened/Closed Ticket, active time to resolve ticket, etc) as well as maintenance (Change Management, CMDB update, etc) activities are continuously improved to meet the client’s demands and objectives. Proactive mechanisms include the definition of governance meetings and their frequency in the SLA. Such meetings address any issues in the M&S operations and guarantee client-provider satisfaction and promote improvement to the current service level. The ITO should also ensure that governance meetings with vendors are properly defined in the Underpinning Contracts so that any changes in the SLA are reflected in these agreements as well.

By means of KPIs and metrics, the ITO/MSP can develop forecast plans and identify methods to improve the service delivery. Hence KPI and metrics reviews can automatically trigger management functions such as capacity and availability before actually being demanded by the client. It is important that the ITO possess metrics which enable it to trigger management functions beforehand so that the client’s satisfaction the service quality are kept at optimal levels at all times.

CSF 8 – Gauge the Customer Satisfaction

The major objectives of a service culture are customer satisfaction and helping customers to achieve their business objectives. As explained in CSF 6, service quality and service satisfaction may be different, since service quality can be measured through metrics, whilst customer satisfaction cannot.

Although the organizational effectiveness as dictated by Nicolaou can be determined from such quality metrics, the BVE is also affected by customer satisfaction. For such reason, the ITO/MSP should ensure that customer satisfaction is defined and measured on a particular schedule within the SLA. This index is obtained from surveys carried out with the client. The results of such surveys should be compared with industry benchmarks and necessary actions are taken accordingly. Such surveys should allow the ITO/MSP to identify strengths and weaknesses so that these can be addressed. Gauging customer satisfaction allows the ITO/MSP to improve both customer-facing and service operation by means of Continual Service Improvement (CSI). The emphasis of CSI is not on assuring real-time service performance; rather it is on identifying where improvements can be made to the existing level of service, or IT performance. Catalysts of CSI are service review meetings and governance meetings held between the ITO/MSP and the client to discuss the current service and future ones. The ITO/MSP should be able to demonstrate to the client how the current service is satisfying the business needs as well as how this can be improved through KPIs.

Final remarks

The contributions of this research consist of both theoretical and practical knowledge. The development of the best practice framework itself is a synthesis of a vast array of literature related to 3 different domains – specifically ERP, ITSM and Outsourcing. This framework succeeds in reconciling these 3 domains into a single practical framework which provides 8 propositions that lead to best practice in ERP maintenance and support outsourcing.

Applications

Such a model can be modified and applied on different outsourcing models including desktop support, infrastructure, and platform. This implies that such a model can also be adapted to as a Service offerings.

Future work

Future work on this model should focus on allowing product owners to quantify the business value of every story or task assigned within a sprint. Such an approach replaces gamification or story points methodologies and provides business with greater transparency on value-driven product delivery.

References

Ahmad, M. & Cuenca, R. (2012). Critical success factors for ERP implementation in SMEs. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing, 4(3), 104-111.

Al-Fawaz, K., Eldabi, T., & Kamal, M. (2011). Investigating factors influencing the decision making process for ERP adoption and implementation: An exploratory case study. In: European, Mediterranean and Middle Eastern Conference on Information Systems 2011. Retrieved 27th May, 2022, from http://www.iseing.org/emcis/EMCISWebsite/EMCIS2011%20Proceedings/SCM15.pdf

Al-Fawaz, K., Eldabi, T., & Naseer, A. (2010). Challenges and influential factors in ERP adoption and implementation. In: European, Mediterranean and Middle Eastern Conference on Information Systems 2010, 1-4.

Arshad, N., May-Lin, Y., & Mohamed, A. (2007). ICT outsourcing: Inherent risks, issues and challenges. WSEAS Transactions on Business and Economics, 4(8), 117-125.

Benaroch, M., Dai, Q., & Kauffman, R. (2010). Should we go our own way? Backsourcing flexibility in IT services contracts. Journal of Management Information Systems, 26(4), 317-358.

Blumberg, M., Cater-Steel, A., Rajaeian, M. M., & Soar, J. (2019). Effective organisational change to achieve successful ITIL implementation. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 32(3), 496–516. https://doi.org/10.1108/jeim-06-2018-0117

BMC. (2020). The Complete Guide to ITIL 4. BMC Blogs. Retrieved 21 May 2022, from https://www.bmc.com/blogs/itil-4/

Bounagui, Y., Mezrioui, A., & Hafiddi, H. (2019). Toward a unified framework for Cloud Computing governance: An approach for evaluating and integrating IT management and governance models. Computer Standards & Interfaces, 62, 98–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csi.2018.09.001

Bradley. J. (2008). Management based critical success factors in the implementation of Enterprise Resource Planning systems. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems, 9, 175-200.

Chou, S. & Chang, Y. (2008). The implementation factors that influence the ERP (enterprise resource planning) benefits. Decision Support Systems, 46(1), 149-157.

Cullen, S., Seddon, P., & Willcocks, L. (2006, February). Managing outsourcing: The lifecycle imperative. (139). London School of Economics and Political Science.

Dan, A., Dumitrescu, C., & Ripeanu, M. (2004, November). Connecting client objectives with resource capabilities: an essential component for grid service managent infrastructures. In: Proceedings of the 2nd international conference on Service oriented computing. 57-64.

Dayal, R. B. & Rana, R. (2019). Adoption of ITIL best practice methodologies in Indian industries. Journal of Statistics and Management Systems, 22(4), 783–790. https://doi.org/10.1080/09720510.2019.1609558

De Sousa, J. (2004). Definition and analysis of critical success factors for ERP implementation projects (Thesis). Retrieved 27th May, 2022, from https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/tesis?codigo=219925

DiMaggio, P. J. & Powell, W. W. (1991). The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Drew, R. (2019). A quantitative analysis of organizational complexity and ITIL implementation challenges (Publication No. 13904460) [Doctoral dissertation, Northcentral University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

DuMoulin, T. (2007, January). The Service Organization Part 3. Pink Elephant Blog. Retrieved May, 28, 2022, from https://blog.pinkelephant.com/blog/the_service_organization_part_3

Ehie, I. & Madsen, M. (2005). Identifying critical issues in enterprise resource planning (ERP) implementation. Computers in Industry, 56(1), 545-557.

Esteves, J. & Pastor, J. (1999, November). An ERP lifecycle-based research agenda. In 1st international workshop in enterprise management & resource planning.

Farrell, M. (2010). Developing a framework for measuring outsourcing performance. In: LRN Conference 2010, 1-8.

Frankova, G., Séguran, M., Gilcher, F., Trabelsi, S., Dörflinger, J., & Aiello, M. (2011). Deriving business processes with service level agreements from early requirements. The Journal of Systems and Software, 84, 1351-1363.

Galup, S., Dattero, R., & Quan, J. (2020). What do agile, lean, and ITIL mean to DevOps? Communications of the ACM, 63(10), 48–53. https://doi.org/10.1145/3372114

Gellings, C. (2006). Contracts for successful outsourcing: Analyzing the impact of pricing structures, penalty. In: Khosrow-Pour, M., (ed). Emerging Trends and Challenges in Information Technology Management, Hershey: Idea Group Publishing. 709-711.

Goo, J. (2010). Structure of service level agreements (SLA) in IT outsourcing: The construct and its measurement. Information Systems Frontier, 12 (2). 185-205.

Goo, J., Kishore, R., & Rao, H (2009). The role of service level agreements in relational management of Information Technology Outsourcing: An empirical study. MIS Quarterly, 33 (1), 119-145.

Goo, J. & Nam, K. (2007). Contract as a source of trust – commitment in successful IT outsourcing relationship: An empirical study. In: HICSS ’07, 3-6 January 2007, Waikoloa. IEEE Computer Society.1-10.

Gottschalk, P. & Solli-Sæther, H. (2005). Critical success factors from IT outsourcing theories: an empirical study. Industrial Management, 105(6), 685-702.

Hung, W., Ho, C., Jou, J., & Kung, K. (2012). Relationship bonding for a better knowledge transfer climate: An ERP implementation research. Decision Support Systems, 52, 406-414.

Iden, J. & Eikebrokk, T. R. (2017, November). The adoption of IT service management in the Nordic countries: Exploring regional differences. In Norsk konferanse for organisasjoners bruk at IT 25(1).

Ifinedo, P., Rapp, B., Ifinedo, A., & Sundberg, K. (2010). Relationships among ERP post-implementation success constructs: An analysis at the organizational level. Computers in Human Behavior, 26, 1136-1148.

Kalbasi, H. (2007). Assessing ERP implementation critical success factors (Dissertation). Retrieved 27th May, 2022, from http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:ltu:diva-45437

Law, C., Chen, C., & Wu, B. (2010). Managing the full ERP life-cycle: Considerations of maintenance and support requirements and IT governance practice as integral elements of the formula for successful ERP adoption. Computers in Industry, 61, 297-308.

Maditinos, D., Chatzoudes, D., & Tsairidis, C. (2011). Factors affecting ERP system implementation effectiveness. Journal of Enterprise Information Management. 25(1), 60-78.

Mandal, P. & Gunasekaran, A. (2003). Issues in implementing ERP: A case study. European Journal of Operational Research, 146(2), 274-283.

McGuire, E. & McKeown, A. (2000). Implementing practical metrics in an outsourcing environment. In: Khosrow-Pour, M., (ed). Challenges of Information Technology Management in the 21st Century, Hershey: Idea Group Publishing. 398-401.

Motwani, J., Subramanian, R., & Gopalakrishna, P. (2005). Critical factors for successful ERP implementation: Exploratory findings from four case studies. Computers in Industry, 56, 529-544.

Obwegeser, N., T. Nielsen, D., & M. Spandet, N. (2019). Continual process improvement for ITIL service operations: A Lean perspective. Information Systems Management, 36(2), 141–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/10580530.2019.1587576

Nachrowi, E., Nurhadryani, Y., & Sukoco, H. (2020). Evaluation of governance and management of information technology services using Cobit 2019 and ITIL 4. Jurnal RESTI (Rekayasa Sistem Dan Teknologi Informasi), 4(4), 764–774. https://doi.org/10.29207/resti.v4i4.2265

Nazimoglu, Ö. & Özsen, Y. (2010). Analysis of risk dynamics in information technology service delivery. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 23(3), 350-364.

Nicolaou, A. (2004). Quality of post-implementation review for enterprise resource planning systems. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems, 5(1), 25-49.

Raflesia, S. P., Surendro, K., & Passarella, R. (2017). The user engagement impact along information technology of infrastructure library (ITIL) adoption. 2017 International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (ICECOS). https://doi.org/10.1109/icecos.2017.8167130

Ruivo, P. & Neto, M. (2011). Sustainable enterprise KPIs and ERP post adoption. CISTI (Iberian Conference on Information Systems, 166-172.

Schaaf, T. (2007). Frameworks for business-driven service level management: A criteria-based comparison of ITIL and NGOSS. In: 2007 2nd IEEE/IFIP International Workshop on Business-Driven IT Management, 65-74.

Shaw, K. (2020). Prioritizing Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL) implementations and identifying critical success factors to improve the probability of success (Publication No. 28153152) [Doctoral dissertation, Capella University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Skibniewski, M. & Ghosh, S. (2009). Determination of key performance indicators with Enterprise Resource Planning systems in engineering construction firms. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 965-978.

Somers, T. & Nelson, K. (2004). A taxonomy of players and activities across the ERP project life cycle. Information, 41, 257-278.

Tan, W., Cater-Steel, A., & Toleman, M. (2009). Implementing IT service management: A case study focusing on critical success factors. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 50(2), 1-12.

Taylor, S., Cannon, D., & Wheeldon, D. (2007). ITIL Service Operation. 1. ed. London: The Stationery Office.

Taylor, S., Iqbal, M., & Nieves, M. (2007). ITIL Service Strategy. 1. ed. London: The Stationery Office.

Taylor, S., Lloyd, V., & Rudd, C. (2007). ITIL Service Design. 1. ed. London: The Stationery Office.

Urikova, O., Ivanochko, I., Kryvinska, N., Zinterhof, P., & Strauss, C. (2012). Managing complex business services in heterogeneous eBusiness ecosystems – Aspect-based research assessment. Procedia Computer Science, 10. 128-135.

Vosburg, J. & Kumar, A. (2001). Managing dirty data in organizations using ERP: Lessons from a case study. Industrial Management, 101(1), 21-31.

Willaert, P. & Willems, J. (2006). Process performance measurement: Identifying KPI’s that link process performance with company strategy. Emerging Trends and Challenges in Information Technology Management, 1, 740-744.

Winkler, T. J. & Wulf, J. (2019). Effectiveness of IT service management capability: Value co-creation and value facilitation mechanisms. Journal of Management Information Systems, 36(2), 639–675. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2019.1599513

Zaydi, M. & Nassereddine, B. (2019). DevSecOps practices for an agile and secure IT service management. Journal of Management Information and Decision Sciences, 22(4), 527-540.

Zhu, Y., Li, Y., Wang, W., & Chen, J. (2010). What leads to post-implementation success of ERP? An empirical study of the Chinese retail industry. International Journal of Information Management, 30, 265-276.